The fact that e-commerce has been a dynamically growing market for more than 20 years is no longer news. However, Covid-19 has led to an explosion in growth rates, the scale of which has surprised many. The share of online purchases in the US jumped to more than 20 percent of total retail sales in 2020, and, according to the latest figures, it was as high as 23.4 percent in December. Globally, online sales are expected to climb to a staggering USD 6.5 trillion a year by 2023. But what about the carbon footprint of this business model?

After the dot.com bubble burst, when the internet was still in its infancy for consumers, online retailing was distributed among a few pioneers like Amazon or Ebay. The barriers to entry for retailers were higher back then and many used these big platforms exclusively. Today, it is easier - and less cost-intensive - to sell products in your own online stores. Solutions for payment processing, web shops, warehousing, corporate design, and advertising on social media are now easy and inexpensive to set up. Nowadays, more companies are using their own marketplaces. This is demonstrated by the pioneer Zalando: fashion can be successfully sold through pre-selected content and coherent campaigns on one’s own platform. We are seeing the development of marketplaces for leased vehicles, pharmacy items, prescription medication or even furniture; each highly specialised to the requirements of both the product and the customer. The growth of the industry, accelerated by Covid-19, has also boosted the share prices of e-commerce companies. Among the high flyers on the stock exchange in 2020 were names such as Amazon, Zalando, Shopify, Zur Rose, Shop Apotheke, MercadoLibre and Meituan Dianping, some of which grew by more than 100 percent. Alibaba's share price came under pressure at the end of last year due to the IPO collapse of its subsidiary ANT. However, its core business, online retailing, continued to grow strongly at 30 percent per year and should continue to have upside potential in the coming years. In addition to these classic online retailers, there are also companies that do not sell goods on the internet themselves, but participate indirectly from the boom. PayPal has always been considered the "gold standard" for online payments. With every year that e-commerce grows, the turnover of the payment service provider also increases. The same applies to Adobe, the software provider for graphic design, planning and conception, which has become indispensable in the field of online advertising. In recent years, hardly any other company has been able to increase its sales as strongly and steadily as Adobe. This success has also been recognised by the stock market with a valuation of USD 230 billion.

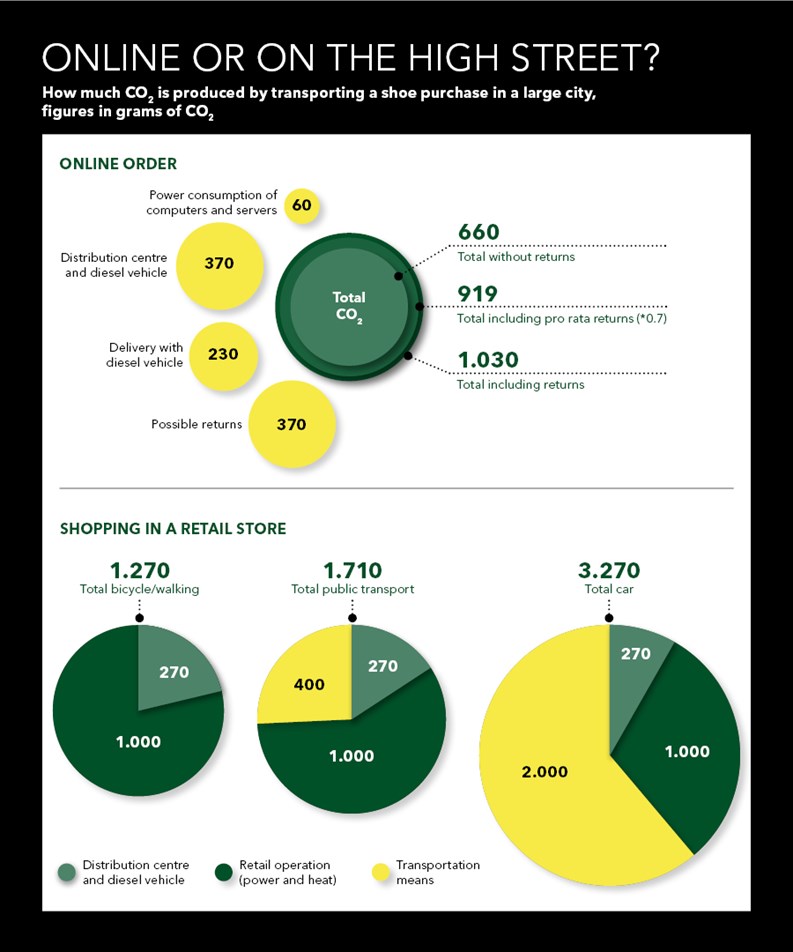

How damaging is e-commerce to the environment?

In Germany alone, online orders result in more than 5 million parcels being delivered every day, and it is a rising trend. On average, every sixth parcel is sent back and these returns generate high CO2 emissions. However, it is difficult to compare this impact on the carbon footprint with that of the high street retail trade, because shopping in a store or supermarket also produces harmful greenhouse gases, for example through the heating and lighting of the sales areas, the delivery of goods to the shops or the customer's journey by car. Anyone wanting to shop in an environmentally-friendly manner should travel by bicycle and make as few returns as possible over the internet. But just how damaging to the environment is e-commerce really and which factors have a significant influence on the environmental footprint? It is not only the mode of transport used, the length of the journey and the fuel consumed for a parcel delivery that are significant factors in the comparison. The warehouse, the operation of data servers and the rate of returns are also significant. In a case study, the Öko-Institut in Berlin, one of Europe's leading scientific consultancies for shaping a sustainable future, put the carbon footprint of the online versus the high-street purchase of a pair of trainers in a large city under the microscope, with some surprising results.

In terms of the manufacturer of the trainers delivering them to a wholesaler, there is virtually no difference between buying online and on the high street. In both cases, delivery is usually by ship or plane, then by haulage companies using diesel trucks. In the case of online retailing, there are slightly more carbon dioxide emissions for server power, handling in the distribution centre, and the customer's PC use when ordering. Up to this point, however, the footprint for a pair of shoes is manageable due to the high economies of scale of the delivery for both distribution channels. Parcel delivery adds 230 g to the total. However, clothing items have the highest return rates with about 0.7 returns per item sold. This means that packaging and returns generate on average another 250 g of CO2. But according to the study, online retailing has a clear advantage. It doesn't need sales areas that have to be provided with electricity and heat. Here, the Öko-Institut estimates 1 kg per pair of shoes sold. Even taking the high average rate of returns into account, only about 919 g of CO2 are produced online, whereas about 1,270 g are produced when shopping on the high street. The study's final result is devastating for the high-street retail trade, because the customer's journey, using an average mode of transport, must also be taken into account.

Graphic: MAINFIRST, source: ÖKO-INSTITUT

In a larger city, this is accomplished either emissions-free on foot or by bicycle, by public transport, or by car. Those who use a car produce a further 2 kg of CO2 with an average journey of four kilometres. In rural areas, the proportion of pedestrians and cyclists drops to almost zero. For a rural journey of 15 kilometres, CO2 emissions rise to more than 7 kg. Although parcel delivery also produces more emissions in rural areas, the emission share of a parcel in a delivery van with hundreds of parcels is almost negligible. In comparison: in the city, delivery accounts for just 230 g of CO2 per parcel. In order to reduce emissions significantly, consumers are therefore advised to use buses, trains or bicycles and, if possible, to move to a large city. Not only is one's personal carbon footprint positively affected by shorter journeys to work and shopping, but we also see lower emissions resulting from the delivery of online parcels. In other parts of the world, the emissions disadvantage of the high street is even more pronounced. In the US, almost all shopping is done by car and, in addition, the average petrol consumption of the cars there is higher. Despite all of this, the ability to combine several purchases should not be discounted. The Öko-Institut's impressive case study refers to the purchase of clothing, the product category with the highest return rates. Although the purchase of clothing, tools or electronics is now relatively common, online purchases of food are still uncharted territory for many people. We can assume that the return rates here should be almost zero and the savings potential for emissions is also significant. Using a single transportation vehicle to make deliveries to 30 households could replace an estimated 15 private car journeys and, in addition, reduce the number of supermarkets displaying their goods in the spotlight for 15 hours a day. Of course, everyone can make their own contribution to reducing CO2 emissions through personal commitment in their everyday lives. Admittedly, we don't live in California, but in northern Europe, where it sometimes pours with rain when it' s 3 degrees outside and where it is utopian for the Müller family of four to do their weekly shopping by bicycle at a supermarket five kilometres away. Therefore, in terms of the carbon footprint it could be worthwhile if we are open to new shopping concepts. The electrification of delivery vehicles has already begun in part and is probably happening faster than with the average person's car. Last but not least, increasing capacity utilisation and shorter delivery routes offer further CO2 savings potential for online retail.

In conclusion, it can be said that investors not only achieve positive performance effects through targeted investments in e-commerce companies, but in combination with a sustainability focus can also positively support the carbon footprint in a targeted manner.

Author: Jan-Christoph Herbst, Portfolio Manager of MainFirst Global Equities Fund, the MainFirst Global Equities Unconstrained Fund & the MainFirst Absolute Return Multi Asset.